In honour of Women’s History Month this month, we delve into the remarkable stories of four extraordinary women from our very own Archive and Microfilm industry, whose contributions spanned various fields, challenging conventions, and leaving indelible marks in history. From Elizabeth Ross-Poyer, one of Parliament’s pioneering archivists, to Barbara Askins, a trailblazing inventor in photographic enhancement, and Winifred Burgess, whose portrait symbolizes the working women of a bygone era, to Christine Granville, a fearless MI6 agent whose exploits rivalled those of any fictional spy. These women’s legacies exemplify courage, ingenuity and resilience, inspiring generations to come.

Elizabeth Ross-Poyer

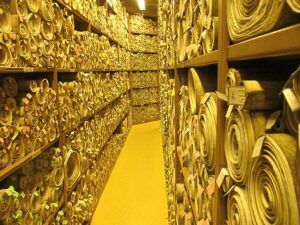

Parliamentary archives by Matt Brown

Born in 1923 in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, Elizabeth Ross Poyser was a history research student at Newnham College in Cambridge before being hired by Maurice Bond as an Assistant Clerk of the Records. Elizabeth needed palaeography and Latin skills and was responsible for running the public search room, preparing documents for microfilming, and indexing the Parchment collection amongst much else. With the House of Lords Record Office only being established in 1946, Elizabeth being hired made her one of the first archivists in Parliament. She stayed in the position until 1965 when she got a new job at Westminster Diocesan Archives, where she was the first female Lay Archivist to be employed by the Catholic Church. She remained there until her retirement.

(Read more about Elizabeth Ross-Poyer here)

Barbara Askins

Barbara Askins

In 1975 former teacher and mother of two Barbara Askins had been asked to develop ways to improve the astronomical and geological photographs that researchers had taken at her position at the Marshall Space Flight Center. She finished the process in 1978, having developed a way of enhancing the quality of underexposed and useless negatives after the film was already developed by using radioactive materials. The process was incredibly successful, and it went on to be used and adapted by other NASA research, as well as X-ray technologies and photograph restoration. She was named the ‘National inventor of the year’ by the Association for the Advancement of Inventions and Innovation in 1979.

(Read more about Barbara Askins here)

Winifred Burgess

Winifred Burgess by Keith Henderson

Whilst the other women on the list today are both people whose contributions were to the processes of archiving and digitisation, Winifred is a subject of it! Between the years 1944 and 1946, the chemical giant ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries) commissioned 20 prominent artists to paint portraits of 55 of the ordinary, working folk from many of their factories as part of an advertising campaign. The portraits were framed and sent around the country as an exhibition known as ‘Portraits of an Industry’. Some of the collection can still be seen at Catalyst Museum, however only 11 of the collection’s whereabouts are known. With 55 paintings in the collection, 44 remain unlocated.

Winifred Burgess is one of the workers whose likeness was captured by Keith Henderson who can be seen at Catalyst. She was a skilled Polymerisation control panel operator at the Winnington works of ICI in 1944. What makes Winifred stand out is that due to the careful record keeping of ICI and the digitisation of the relevant files, we can see her worker’s record cards along with her portrait and the information that she provided when she was painted, giving us a clearer picture of her working life from an era when it was still quite new for women to be in the workplace.

(Read more about Winifred Burgess here)

Christine Granville

Said to be the inspiration for the James Bond character Vesper Lynd, Krystyna Janina Skarbek was the first female MI6 agent, as well as the longest serving. When she heard in 1939 that her homeland of Poland had been invaded by the Nazis, Skarbek’s reaction was to head to London, to MI6, and demanded a role in active service. What followed was a career of daring and trickery that earned her the accolade as Churchills’ “Favourite Spy”. With a combination of charm, contacts and courage, Granville (As she became known) managed to smuggle information, radio codes and coding books- As well as microfilm, which she would conceal inside her gloves or embed into blocks of shaving soap.

Christine Granville, born Krystyna Janina Skarbek

Amongst some of the information that she managed to send back to Churchill was the first microfilm evidence of Operation Barbarossa, the planned Nazi invasion of their allied Soviet Union.

She was awarded an OBE in 1947, as well as the George Medal, the 1939-1945 Star, the Africa Star, the Italy Star, the France and Germany Star, the War Medal, and the Croix de Guerre. Tragically it wasn’t a mission of espionage that ended the life of Christine Granville, but a scorned suitor, stabbing her in the chest in the Shellbourne hotel in 1952. An English heritage blue plaque marks this spot today, having been placed in 2020.

(Read more about Christine Granville here)

Comments are closed.