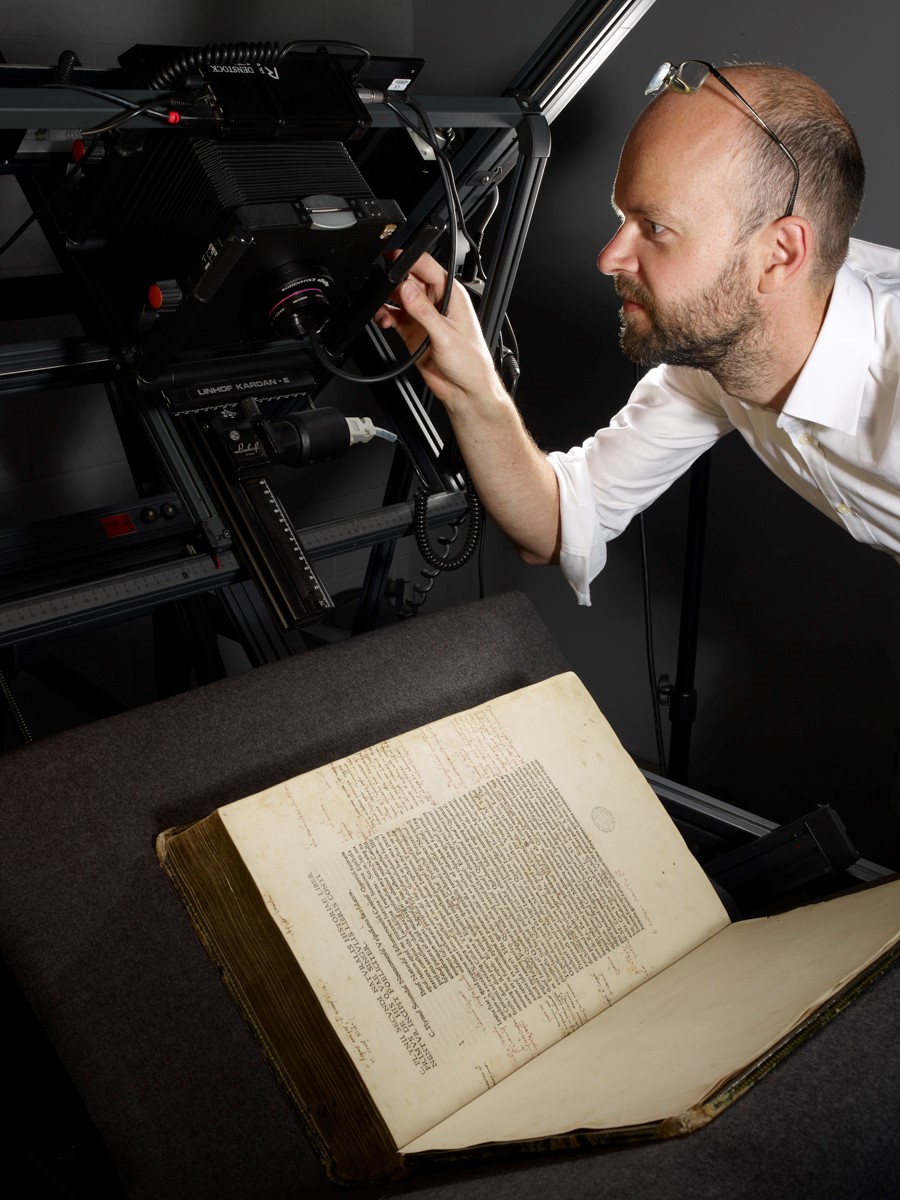

The Bodleian Library was established in 1602 and is the second largest library in the UK. It is a legal deposit library, holding approximately 13 million printed items, as well as extensive collections of manuscripts, many of which originate from the Middle Ages. The Bodleian is home to manuscripts authored by J. R. R. Tolkien, Jane Austen and Mary Shelley. Notable treasures include four engrossments of Magna Carta, the first printed volume: The Guttenberg Bible, as well as original calotypes and negatives made by photography pioneer, William Henry Fox Talbot. It’s a great privilege to work with such an incredible variety of material.

The Bodleian has a team of five photographers, each with at least ten years of experience in the capture of library material. The Bodleian almost exclusively photograph with Phase One digital backs ranging from 39 to 100 million pixels. Our studio has a variety of medium and large format cameras and lenses, mounted either on conventional wall mounted copy stands or by specialist book cradles. Our books and manuscripts are, for the most part, supported by Grazer Conservation Copy Stands during photography. Digitally controlled studio flash units are used for all of our work.

Why did you embark on the project?

For several years the Bodleian has participated in large collaborative digitisation projects, often with the generous support of the Polonsky Foundation. We felt that it was important to establish a common set of image quality expectations between the Bodleian and it’s partner institutions. In doing so, we hope that we can ensure that images produced for large-scale digitisation projects will be of the highest possible quality and consistent with each other. Given that these images are likely to be presented in a shared platform this consistency is of great importance.

It is striking to see the differences between reproductions which are being made in the Bodleian Studio today, and those made only fifteen years ago. The differences are equally or even more notable when comparing images photographed from similar material by different institutions. It is important to aim for constancy: page-to-page when digitising a volume, volume to volume within a collection or project, between collections in order to achieve a consistent archive and ultimately between the images made by other institutions. This is particularly pertinent now that images can be viewed using a shared framework such as the IIIF Mirador tool.

Clearly our photography has developed significantly since our first digital reproductions in 2000. This is due to a combination of reasons: advances in camera and lighting technology, improvements in specialist reproduction photography technique and through meeting the increased expectations of our clients.

In order to objectively assess the quality of our images, the Bodleian felt that it should follow the example of peer institutions by researching the two most recognised Guidelines for the digitisation of two-dimensional cultural heritage materials: The Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative or FADGI and the Metamorfoze Preservation Imaging Guidelines.

The project would involve: researching the guidelines, rewriting them so that they could be more easily understood by photographers, assessing the accuracy of our current images in accordance with the guidelines and finally developing a workflow which could be used to create images which were in almost all cases compliant at the highest performance levels.

What standard have you chosen to adhere to – FADGI, Metamorfoze or ISO and what level?

Though this may sound surprising, given that I’ve been invited to contribute to this blog, the Bodleian do not claim that they are fully compliant with either of the Guidelines at their highest performance levels. There are however, sound, justifiable reasons for this.

For almost every image quality element listed in the Guidelines’ parameter tables, the Bodleian aims to comply at the highest performance level, but there are two prominent exceptions as well as some other stipulations which we choose not to comply with. These stipulations are not listed in the guidelines’ parameters tables but are requirements nonetheless. Our exceptions to adhering to these requirements and the justifications for them are described in the document which I was asked to produce for the Bodleian.

At first did you find the complexity of the standards daunting?

Having worked at the Bodleian as a photographer of special collections material since 2005, I’ve been aware of the guidelines for a few years. However, like many of the talented photographers which I’ve met working in the same field, I considered the Guidelines extremely daunting to read in detail. Both documents are long and complex.

The authors of the guidelines are, in the case of FADGI, a colour scientist and in the case of Metamorfoze, an image analyst. Requirements are therefore difficult for a photographer to understand and therefore apply in their work. For instance, you won’t find any mention of megapixels or apertures in the Guidelines. There’s no information regarding lighting placement or suitable modifiers.

Though the FADGI Guidelines provide a reasonably comprehensive resource, detailing the equipment and, more broadly, the processes which should be used for the digitisation of special collections material, ultimately both documents focus on the what and not the how.

At their core, both guidelines specify a series of measurable ‘parameters’ and ‘aimpoints’ which must be achieved or exceeded in order to meet a specified ‘performance level’.

Most of these parameters are highly technical and can only be assessed through the analysis of calibrated technical targets using software either developed in collaboration with or approved by the authors of the guidelines.

However, it is first necessary to understand the parameters stated in the guidelines and their aimpoints.

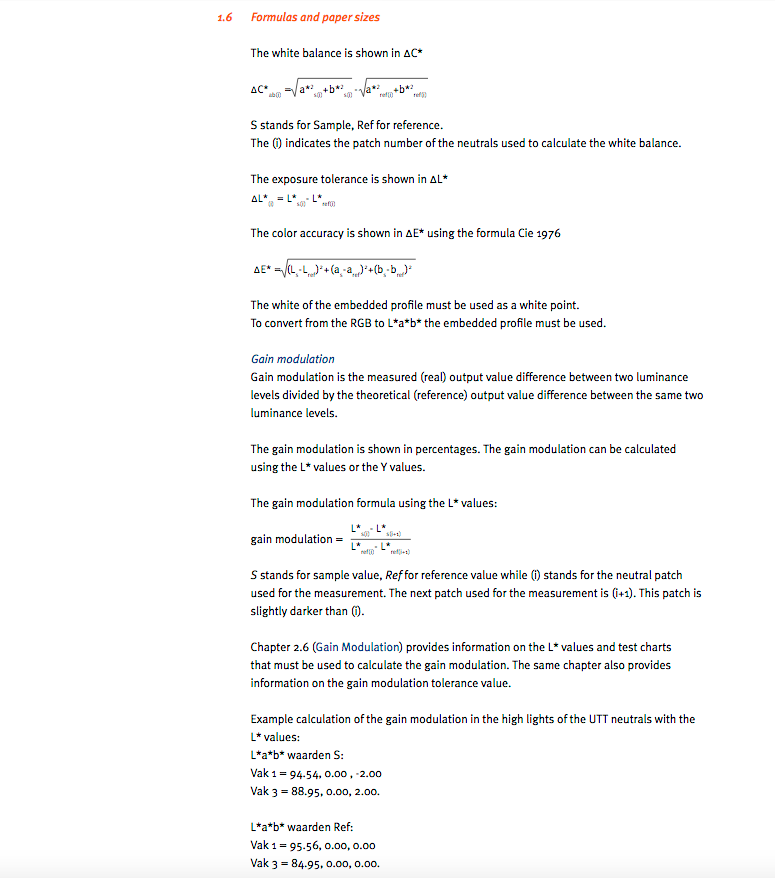

Technical definitions and acronyms are used to describe the many different measurable analysis elements and for many of the parameters. For instance, terms that photographers are familiar with such as resolution are defined in the Guidelines as sampling rate, while the presence of noise in an image is referred to as standard deviation. Measurements are calculated through the use of complex mathematical equations. Page 14 of the Metamorfoze Guidelines are particularly off-putting for the non mathematically minded.

Though initially they may seem daunting to read, in essence, the parameters tables concern aspects which all photographers are familiar with: resolution, colour, exposure and sharpness.

Surprisingly and frustratingly, there is little or no explanation in the guidelines of either what the parameters are or how to measure them and after fairly extensive research; I haven’t been able to find a resource that explains each of the parameters fully and how to use them practically.

In order to make the Guidelines more accessible to those interested in using them, the document, which I have produced, explains each and every parameter in turn, using terminology which photographers are familiar with. I’ve also provided two technical appendices in order to explain the units of measurement used by the guidelines for their description of parameters concerning colour (L*a*b*) and sharpness (MTF and SFR).

The aimpoints for each of the parameters are then compared side by side, highlighting differences between the Guidelines’ requirements.

In addition to the parameters tables, the many non-measurable requirements stated in the Guidelines are also described in the document. This is important, as it should not be considered that an image is compliant solely due to the fact that it has met or exceed the aimpoints in the parameters tables.

Specifications concerning the composition of an image are also defined by the guidelines. For instance, Metamorfoze states that ‘…images must be captured per opening, which means the left and right page must be captured at the same time. This applies to both bound and loose-leaf materials.’ This is impossible to achieve with the book cradles which we use at the Bodleian, which only allow for the capture of individual pages rather than two facing pages. Naturally the safe handling of special collections material is of paramount importance and we would not consider opening volumes to 180 degrees. This is an example of one of the eight elements from the Guidelines which prevent the Bodleian from claiming full compliance.

Once you had gained an understanding of the standard how easy did you find the process?

One might assume that the process of analysing images of technical targets should be straightforward and standardised. Frustratingly however, there is currently no industry standard solution. During this project I researched seven software solutions, some of which are commercially available and others that are free to use. There are at least 12 different technical targets which are commonly used in the digitisation of library material. These targets can be split in to two groups: Object level targets, which are captured alongside the original during photography, and device-level targets which are typically larger and allow for the analysis of a greater number of parameters and at a higher level of accuracy.

Analysing all of the image quality parameters accurately is therefore extremely confusing and laborious.

How have you integrated the Zeutschel QM Tool into your workflow and is it proving a valuable tool?

The Universal Test Target is perhaps the most comprehensive technical target available for two-dimensional photography. This single A3 sized device level target is capable of measuring every one of the parameters listed in the FADGI and Metamorfoze Guidelines. For the photography of larger originals, technical targets consisting of multiple UTTs side-by-side are also available.

In addition to the ColorChecker Digital SG target, commonly used for reproduction photography, the UTT is able to measure parameters such as spatial frequency response (optical sharpness), reproduction scale accuracy and geometric distortion. In essence, this is a target constructed from a number of smaller targets and has been meticulously designed by the author of the Metamorfoze Guidelines. In fact, the use of this target, and its associated Reference File is stated as a requirement in order to claim full compliance with Metamorfoze.

To compliment this technical target, Zeutschel have created QM-Tool; a software application which is capable of analysing images photographed from the UTT and providing confirmation regarding the performance levels for each of the parameters. Sadly, though the Bodleian has acquired and intends to use this solution for the analysis of our images, due to the current restrictions, the Bodleian Studio is currently closed and I haven’t yet been able to explore this application further.

What is the impact on your workflow with regard to additional processes or time to throughput jobs?

Up to this point my analysis process has involved using three software applications and two different technical targets so, all being well, adopting QM-Tool in to our workflow will significantly reduce the time and complexity involved in performing benchmark tests.

What benefits does applying to the standard bring?

Clearly, by complying with the majority of the image quality parameters, a high level of accuracy between original and reproduction can be assured.

In some cases funding for both small and large-scale digitisation programmes may only be provided to institutions which claim to be compliant with the Guidelines at the highest performance levels. This is another important benefit to compliance.

What would your recommendation be to other organisations?

We don’t claim that our approach is perfect, nor do we consider that it follows either of the Guidelines to the letter. We do however feel confident in the accuracy and consistency of our images, and many elements from the guidelines have aided us in attaining this standard. Our take on using the Guidelines is to adhere to the aspects that provide the best outcome for our end-users and ultimately to produce objectively accurate reproductions.

Though further analysis in our Studio using QM Tool will be required before the document which I’ve written for the Bodleian can be finalised, if you would like to read the document in its current form, or if you’d like to ask any questions relating to the Guidelines, please feel free to contact me. One of the primary reasons for embarking on our imaging standards review was to share our findings with other institutions in the hope that our openness will encourage others to share their approaches and contribute to a community of shared expertise. You can do this by commenting below or by contacting John Barrett at john.barrett@bodleian.ox.ac.uk

Though further analysis in our Studio using QM Tool will be required before the document which I’ve written for the Bodleian can be finalised, if you would like to read the document in its current form, or if you’d like to ask any questions relating to the Guidelines, please feel free to contact me. One of the primary reasons for embarking on our imaging standards review was to share our findings with other institutions in the hope that our openness will encourage others to share their approaches and contribute to a community of shared expertise. You can do this by commenting below or by contacting John Barrett at john.barrett@bodleian.ox.ac.uk

If you have any interesting topics or projects you’d like to submit to our Blog Page then please contacts us.

Visit the Bodleian’s Digital Library

Genus would like to thank our Guest Blogger John Barrett – Imaging Services – Photographer at The Bodleian Libraries for his contribution to this Blog.

Comments are closed.